Antihypertensive

medications and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: a systematic review

Shadman

Newaz 1*, Fahmida Zaman 1, Ayesha Noor 2, Promita

Das 3, Fariha Tanjim 1, Farhana Ferdaus Raisa 1,

Muhsina Farhat Lubaba 1, Jannat Ara Tina 1, Supritom

Sarker1

1 Tangail

Medical College, Tangail, Bangladesh

2 Department

of Pharmacy, Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3 Dinajpur

Medical College, Dinajpur, Bangladesh

Corresponding Author: Shadman

Newaz

* Email: shadmannewaz11@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Emerging evidence

suggests that antihypertensive medications may influence the risk, progression,

and survival outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, findings

across studies remain inconsistent. This systematic review aims to evaluate and

synthesize current data on the associations between different classes of

antihypertensive drugs and liver cancer outcomes.

Materials and methods: A systematic review was conducted, incorporating randomized controlled

trials, cohort studies, retrospective analyses, and in vitro studies that

investigated the relationship between antihypertensive medications and HCC.

Extracted data included study design, population characteristics, drug

categories, primary outcomes, and study limitations.

Results: Nine studies met the inclusion criteria, encompassing diverse study

designs and patient populations. Renin-angiotensin system (RAS)

inhibitors—including ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers

(ARBs)—were most consistently associated with reduced HCC incidence and

improved survival. Thiazide diuretics demonstrated potential protective effects

in genetic studies, though results were mixed in larger population-based

analyses. Beta-blockers yielded inconclusive evidence: while some studies

linked them to increased HCC risk, others found neutral or beneficial effects,

particularly for non-selective Beta-blockers in patients with established HCC.

Additionally, one preclinical study highlighted possible anti-cancer activity

of agents like chlorpromazine and prazosin.

Conclusion: RAS inhibitors show the strongest and most consistent evidence for a

protective effect against HCC development and progression among

antihypertensive drug classes. Certain non-selective Beta-blockers may also

offer survival benefits in specific patient populations. However, conflicting

findings and methodological limitations across studies underscore the need for

high-quality prospective research to confirm these associations and inform

clinical practice

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Antihypertensive drug, ACE inhibitors, ARBs,

Beta-blockers, Diuretics, Liver cancer

Introduction

Hypertension is a widespread global health

concern and a primary contributor to cardiovascular disease (1–4). Globally, approximately

1.28 billion adults aged 30 to 79 are affected by hypertension (5), which is recognized as the

leading risk factor for mortality worldwide (5,6). In parallel, liver cancer

continues to pose a major global health challenge. As of 2024, it ranks as the

sixth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths,

accounting for nearly 800,000 fatalities each year. Hepatocellular carcinoma

(HCC) constitutes about 90% of all primary liver cancers (7,8).

Most individuals diagnosed with stage 1

hypertension or higher are treated with antihypertensive medications (9–11). Common

first-line agents include Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEIs),

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs), Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs), and

thiazide diuretics. Other medications such as Beta-blockers, loop diuretics,

vasodilators, and α-blockers are typically used as second-line treatments

in particular clinical contexts (12,13). Research

exploring the relationship between antihypertensive therapies and cancer risk

has produced inconsistent findings. These variations may be influenced by

geographic location, preexisting conditions, concurrent comorbidities, and

unknown underlying mechanisms.

Specifically, the connection between

antihypertensive drug use and liver cancer has not been extensively studied,

and current data do not establish a definitive causal link (14–16). Nevertheless,

the relationship is believed to be multifactorial and remains under

investigation. Some studies suggest that certain antihypertensive drug classes

may influence tumor development (17–20). The

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS), for instance, has been implicated

in cancer biology beyond its role in blood pressure regulation. It is

hypothesized that modulation of Angiotensin II activity by drugs like ACEIs and

ARBs could affect angiogenesis (21–24) and thereby

influence liver tumorigenesis.

ACEIs and ARBs have been associated with

reduced cancer incidence and improved survival in several observational studies

(25–27). Moreover,

Beta-blockers, thiazide diuretics, and some CCBs have demonstrated

anti-angiogenic properties, which could influence tumor growth (27,28). Conversely,

other research—such as one case-control study—reported a slight increase in

colorectal cancer risk with ACEI and ARB use, raising concerns about potential

implications for liver metastasis (29).

Given the conflicting data and the absence of

definitive conclusions, a significant research gap persists regarding the role

of blood pressure medications in HCC development (25,27,28,30). The potential

interactions between antihypertensive agents and liver cancer remain

underexplored (31,32). This review

seeks to evaluate both the direct and indirect roles of these medications in

HCC, examine the conflicting effects of ACEIs and ARBs and their clinical

implications, address gaps in current knowledge, and highlight new directions

for future research aimed at clarifying these associations.

Materials and methods

Study Design

and Protocol Registration

This systematic review was guided by a pre-established protocol

registered on the Open Science Framework. The review process adhered strictly

to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

(PRISMA) guidelines to ensure transparent and rigorous reporting.

Eligibility

Criteria

Studies published between 1st January 2015 and 28th

February 2025 were eligible for inclusion if they explored the association

between antihypertensive medications and liver cancer-related outcomes.

Included study designs comprised randomized controlled trials, cohort and

case-control studies, and observational research. Only articles published in

English were considered. To be included, studies had to focus on individuals

with hypertension and assess the effects of antihypertensive drugs on liver

cancer risk, progression, or mortality. Studies were excluded if they were

non-English, lacked extractable data, were protocols only, or discussed other

cancer types without clear relevance to liver cancer in hypertensive patients.

Research published before 2015 was also excluded.

Search Strategy

An extensive literature search was conducted using four prominent

electronic databases: PubMed, ScienceDirect, the Cochrane Central Register of

Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Mendeley. The search employed a mix of Medical

Subject Headings (MeSH) and keyword-based queries focused on antihypertensive

drugs, liver cancer, and hypertension.

Key search terms included:

·

For drug

types: "ACE inhibitors" OR "angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitors" OR "ARBs" OR "angiotensin II receptor

blockers" OR "beta-blockers" OR "calcium channel

blockers" OR "diuretics" OR "renin-angiotensin system"

OR "antihypertensive agents"

·

For

cancer: "liver cancer" OR "hepatocellular carcinoma" OR

"liver carcinoma" OR "hepatic neoplasms"

·

Subtypes:

"hepatocellular carcinoma" OR "cholangiocarcinoma" OR

"liver metastasis"

The search was broadened using additional terms such as:

·

"liver cancer incidence," "progression,"

"recurrence," "mortality," and "survival"

·

Combined

queries like "hypertension treatment" OR "cardiovascular

drugs" AND "liver cancer risk," and "antihypertensive side

effects" AND "liver cancer survival"

Reference lists from key studies and relevant reviews were manually

screened to capture any overlooked studies. The initial database search was

conducted on January 26, 2025, and updated on February 26, 2025.

Screening and

Data Extraction

The screening process was conducted using Rayyan software to facilitate

duplicate removal and streamline the title/abstract screening phase. Two

independent reviewers (JT and FT) conducted the initial screening, and any

disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer (SS).

Full-text articles of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and reviewed

for final inclusion.

Data extraction was carried out using a structured Excel template, which

collected information on study design, sample population, drug class, liver

cancer outcomes, and key findings. Extraction was primarily handled by SN, with

independent verification of 50% of the data entries by FZ and PD for quality

assurance.

Quality

Assessment

Although the review primarily aimed to summarize the breadth of available

evidence rather than perform a critical quality assessment, potential

limitations and sources of bias in each study were noted descriptively. Where

applicable, formal tools such as the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale were used to

appraise the quality of cohort and case-control studies. No studies were

excluded based on quality scores alone.

Data Synthesis

Due to substantial heterogeneity in the

included studies—across study design, sample demographics, drug classification,

outcome measurement, and follow-up duration—a meta-analytic approach was not

feasible. While formal statistical heterogeneity (e.g., I²) could not be

calculated, qualitative indicators of variability such as differing comparator

groups, inconsistent effect directionality, and variation in drug dosage/timing

were noted across studies.

As a result, findings were synthesized narratively to provide a comprehensive

overview of the relationships between different classes of antihypertensive

medications and liver cancer outcomes. This approach allowed for thematic

comparison across diverse methodologies and helped contextualize apparent

contradictions in the literature.

Bias Assessment

To evaluate potential biases in the included studies, recognized

assessment frameworks were used. The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was applied to

analyze aspects such as selection, performance, detection, and reporting bias.

Each study underwent independent review by multiple researchers to enhance

objectivity and consistency. This process aimed to thoroughly explore and

report the possible biases affecting study outcomes and to support the

credibility of the review's conclusions.

Results

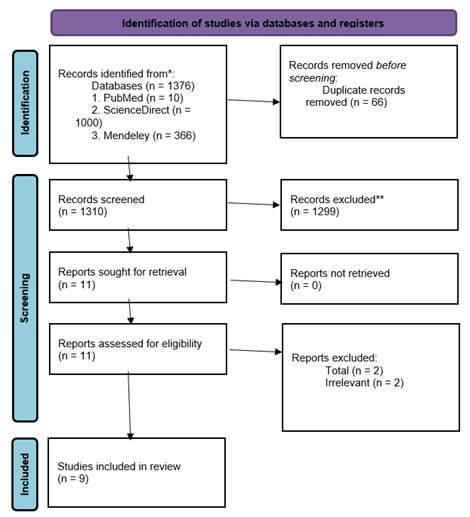

The selection process for this systematic

review, as outlined in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1), aimed to determine

the potential effects of antihypertensive drugs on liver cancer outcomes. A

total of 1,376 records were retrieved from three databases: PubMed (10),

ScienceDirect (1,000), and Mendeley (366). After removing 66 duplicates, 1,310

records were screened by title and abstract. Following this, 1,299 records were

excluded due to irrelevance or not meeting the inclusion criteria. 11 full-text

articles were reviewed, with 2 subsequently excluded for being unrelated,

leaving 9 studies that met the eligibility criteria and were included in the

final review. This systematic selection approach promotes transparency and

methodological rigor (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prisma flow diagram illustrating the study selection process. The

flow diagram outlines the systematic selection of studies included in this

review. A total of 1,376 records were identified through database searches

(PubMed: 10, ScienceDirect: 1,000, Mendeley: 366). After removing 66

duplicates, 1,310 records were screened by title and abstract. Of these, 1,299

were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Eleven full-text articles

were assessed for eligibility, and two were excluded for being unrelated to

liver cancer outcomes. Ultimately, nine studies were included in the

qualitative synthesis. This structured screening process ensured methodological

transparency and adherence to PRISMA guidelines.

The geographical distribution of the included

studies (Table 1) indicates a predominance of research conducted in high-income

countries. The United States accounted for the highest number of studies (n =

2). Additionally, one study each originated from the United Kingdom, South

Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Germany. One study was broadly categorized under the

region of Europe and East Asia.

Table 1.

Country

distribution of included studies.

|

Country

Name

|

Total

Count

|

|

United

States

|

2

|

|

Europe

& East Asia

|

1

|

|

United

Kingdom

|

1

|

|

South

Korea

|

1

|

|

Spain

|

1

|

|

Sweden

|

1

|

|

Germany

|

1

|

The summary presented in (Table 2) outlines

the distribution of different study designs included in the dataset. Randomized

controlled trials (RCTs) are the most frequently reported, accounting for three

out of nine studies. Retrospective cohort studies appear twice, while each of

the following designs is represented once: standard cohort study, longitudinal

cohort study with repeated measures, in-vitro experimental study, and

regression analysis. This reflects a diverse mix of research methodologies, with

a slight predominance of experimental approaches, particularly RCTs, which are

widely regarded as the benchmark for evaluating clinical interventions.

Table 2. Methodological

designs of included studies.

|

Study Design

|

Total count

|

|

Randomized

controlled trial

|

3

|

|

Retrospective

cohort study

|

2

|

|

Cohort study

|

1

|

|

Regression

analysis

|

1

|

|

In-vitro

experimental study

|

1

|

|

Longitudinal

cohort study (repeated measures)

|

1

|

Key Characteristics of Included Studies

This table (Table 3) presents the basic

features of each study, providing context for evaluating the study populations,

methodologies, and limitations. These elements help interpret the results and

assess the risk of bias.

Table 3. Key characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

|

References

|

Country

|

Design

|

Total Participants

|

Age

|

Gender

|

Limitations

|

|

(27)

|

Europe and East Asia

|

Randomized control trial

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

Both male and female

|

MR assumptions, lack of clinical data, limited generalizability

|

|

(33)

|

United Kingdom

|

Longitudinal cohort study

|

2399

|

>35

|

Both male and female

|

Observational design, adherence uncertainty, residual confounding

|

|

(34)

|

U.S.

|

Randomized controlled trial

|

2733

|

60 ± 9.9

|

Both male and female

|

Selection bias, loss to follow-up, confounding

|

|

(35)

|

South Korea

|

Randomized control trial

|

32,692

|

50–60 (avg 58)

|

Comparison

|

Retrospective data, adherence bias, ethnic limitations

|

|

(36)

|

Spain

|

Retrospective cohort study

|

153

|

39–86

|

Majority Child-Pugh

|

Lack of RCTs, pharmacological interactions, genetic variability

|

|

(37)

|

Not Applicable

|

Retrospective cohort study

|

Not applicable

|

Not applicable

|

Comparison

|

Not specified

|

|

(38)

|

United States

|

In vitro experimental study

|

Not applicable

|

Not applicable

|

Not applicable

|

In vitro only, no apoptosis mechanism confirmed

|

|

(39)

|

Sweden

|

Cohort study

|

2104

|

30–94

|

Not applicable

|

Observational design, adherence uncertainty, confounding

|

|

(40)

|

Germany

|

Regression analysis

|

349,210

|

Not applicable

|

Comparison

|

Lifestyle data missing, short follow-up, selection bias

|

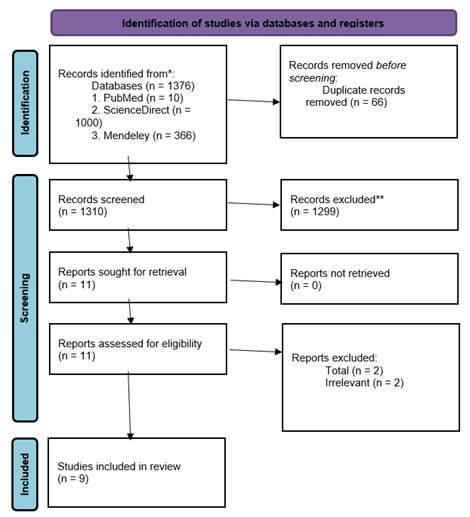

Figure 2 displays the risk of bias assessment

for the nine studies included in this review, evaluated across six

methodological domains: participant selection, confounding variables,

measurement of exposure, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome

data, and selective outcome reporting. Several studies demonstrated a high risk

of bias in multiple domains, particularly in areas such as selective reporting

and participant selection. Some studies showed predominantly unclear risks,

often due to insufficient reporting of study methods. A few studies exhibited

low risk across most domains, particularly in measurement and blinding.

Overall, the figure highlights substantial variation in study quality,

emphasizing the need for cautious interpretation of findings due to

methodological inconsistencies.

Figure 2. Risk of bias assessment among studies. This figure summarizes the

domain-specific risk of bias for each included study using six criteria:

D1—Selection of Participants, D2—Confounding Variables, D3—Measurement of

Exposure, D4—Blinding of Outcome Assessment, D5—Incomplete Outcome Data, and

D6—Selective Outcome Reporting. Risk levels are indicated by symbols: red (✖) for high risk, green (✔) for low risk, yellow (▲) for unclear risk, and gray diamonds (◆) for not applicable. Overall risk reflects

the cumulative assessment across all domains.

Main Findings of the Studies on the Basis

of Antihypertensive Drugs Classification

This table (Table 4) categorizes the main

findings according to antihypertensive drug classes with serial numbers

referencing specific studies.

Table 4. Main findings of

the studies based on antihypertensive drugs classification.

|

Drug Class

|

Findings

|

References

|

|

Thiazide

Diuretics

|

Associated with decreased HCC risk in both Europeans and East

Asians.

|

(27)

|

|

Beta-Blockers

(BBs)

|

Increased HCC risk in Europeans; No association in UK study;

Reduced liver cancer mortality in Sweden (non-selective BBs better).

|

(27,33,39)

|

|

ACE

Inhibitors (ACEIs)

|

No significant association with HCC risk.

|

(33,40)

|

|

Angiotensin

II Receptor Blockers (ARBs)

|

Reduced recurrence and improved outcomes in HCC patients

following radiofrequency ablation (RFA) (study 5); Increased prostate cancer

risk (study 9).

|

(36,40)

|

|

Renin-Angiotensin

System (RAS) Inhibitors

|

Reduced HCC risk with long-term use in patients with hypertension

and liver disease.

|

(35)

|

|

Diuretics

(General)

|

Associated with increased liver and hematopoietic cancer risks;

decreased prostate and skin cancer risk.

|

(40)

|

|

Calcium

Channel Blockers (CCBs)

|

No significant cancer association.

|

(40)

|

|

Others

(Prazosin, Chlorpromazine)

|

Reduced viability in HCC cell lines; potential cytotoxic effect

in vitro.

|

(38)

|

|

Non-Classified

(e.g., Sorafenib)

|

Adverse hepatic effects not linked to treatment duration or

response.

|

(37)

|

Summary of

Findings (Table 4)

·

Thiazide diuretics demonstrated a

potential protective effect against hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in both

European and East Asian populations (27).

·

Beta-blockers demonstrated inconsistent associations with hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) outcomes across studies. One study reported an increased risk

of HCC among European users (27), while another conducted in the UK found no

significant protective effect (33). In contrast, a Swedish study observed reduced liver

cancer mortality, particularly with the use of non-selective beta-blockers (39). These conflicting results may be due to differences

in beta-blocker type (selective vs. non-selective), patient populations, study

design, or unmeasured confounding factors.

·

ACE inhibitors and calcium channel

blockers (CCBs) were not significantly associated with liver cancer outcomes in

the reviewed studies (33,40).

·

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

provided supportive benefits when used alongside radiofrequency ablation in HCC

management (36,40); however, one

extensive cohort study noted an increased risk of prostate cancer linked to ARB

use (40).

·

Renin-angiotensin system (RAS)

inhibitors, as a broader class, were associated with a decreased risk of HCC

with prolonged use in a South Korean cohort (35).

·

Diuretics, when not categorized into

specific subtypes, were linked with an elevated risk of liver cancer in a large

German regression analysis (40), suggesting outcomes may depend heavily on drug subclass and

patient context.

·

Prazosin and chlorpromazine,

evaluated in vitro, exhibited promising anti-tumor activity, implying potential

for drug repurposing, though clinical evidence is still lacking (38).

·

Sorafenib was associated with

hepatic side effects regardless of treatment duration or response, warranting

caution when used in patients with liver impairment (37).

Influencing Factors in the Relationship Between Antihypertensive Drugs

and Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Table below (Table 5) includes influencing factors for liver cancer due

to hypertension management.

Table 5. Influencing factors in the relationship

between antihypertensive drugs and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

|

References

|

Influencing Factors

|

|

(27)

|

Genetic variants, pleiotropy, ethnic differences, hypertension

and liver health, drug metabolism.

|

|

(33)

|

Hypertension, diabetes, liver disease, alcohol use, obesity,

smoking, viral hepatitis, medication adherence, and exposure definition.

|

|

(34)

|

Age, gender, cause of cirrhosis, liver function, comorbidities,

surveillance, and medical management.

|

|

(35)

|

Underlying hypertension and liver disease, medication adherence,

comorbidities (diabetes, obesity), demographics, smoking, alcohol

consumption.

|

|

(36)

|

Tumor characteristics, liver cirrhosis and fibrosis,

comorbidities (renal and cardiovascular health), and pharmacokinetics of

ARBs.

|

|

(37)

|

Pre-existing arterial hypertension (AH).

|

|

(38)

|

Oxidative stress, IC₅₀ concentrations of tested drugs

(chlorpromazine and prazosin).

|

|

(39)

|

Type of Beta-blocker used, liver condition, cancer stage.

|

|

(40)

|

Drug type, comorbidities, large sample size, unaccounted

lifestyle factors, combination therapies.

|

Potential

Effect Modifiers

The studies

reviewed highlighted several categories of factors that may modify the

relationship between antihypertensive medications and hepatocellular carcinoma

(HCC) outcomes:

·

Metabolic and Genetic Factors:

Genetic variability and metabolic differences—including liver-specific drug

metabolism—were noted as possible reasons for differential drug responses

across populations.

·

Comorbid Conditions: Common

coexisting diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic liver disease,

obesity, and cardiovascular disorders were frequently identified as

confounders.

·

Behavioral and Lifestyle Factors:

Alcohol use, smoking, and dietary patterns were recognized as important but

inconsistently measured modifiers of HCC risk.

·

Treatment-Related Factors:

Characteristics such as pharmacokinetics, medication adherence, and the

specific class of antihypertensive drug (e.g., ACE inhibitors, ARBs,

β-blockers, diuretics) were central to observed variations in outcomes.

·

Tumor-Specific Variables: Clinical

features of the tumor—such as size, stage, and vascular invasion—were shown to

influence the impact of antihypertensives when used as adjuncts in HCC therapy.

·

Study and Population Heterogeneity:

Variability in data collection methods, patient demographics, and study design

also contributed to bias and limited comparability across studies.

Discussion

The relationship between antihypertensive

medications and liver cancer remains controversial. While most studies report

no significant association, some have identified links involving common

antihypertensives such as ACE inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers

(ARB), calcium channel blockers (CCB), and diuretics. Among these, ARBs have

shown a potential protective effect against liver cancer. This is hypothesized

to result from inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system, particularly the

angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R), allowing unopposed stimulation of AT2R,

which may exert anti-proliferative and anti-angiogenic effects (27,41,42).

Experimental models, such as the rat liver

perfusion model, suggest that hyperosmolarity-induced upregulation of the

miR-15/107 family and miR-141-3p may influence liver cell apoptosis and

proliferation (40).

Diuretics have also been associated with

increased liver cancer risk in some studies, with Cox regression analyses

indicating a positive correlation (40).

Additionally, in patients with pre-existing

liver conditions like hepatic steatosis, antihypertensives—particularly CCBs,

ARBs, and ACEis—have been linked to disease progression and elevated liver

cancer risk (43).

This systematic review highlights the nuanced and multifactorial nature

of the association between antihypertensive drugs and HCC. Certain medications,

such as thiazide diuretics, were found to reduce HCC risk in both European and

East Asian populations (27). Similarly, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors—including ACE inhibitors

and ARBs—were linked to improved progression-free survival and lower HCC

incidence in South Korean cohorts (35,36). Evidence from Sweden further suggested that non-selective Beta-blockers

may lower liver cancer mortality (39).

Conversely, some findings raised caution. A German regression analysis

indicated a positive relationship between diuretics and liver cancer risk (40), which contradicts results from a Mendelian randomization study (27). Similarly, Beta-blockers were associated with increased HCC risk in

Europeans (27), while other studies either found no association (33) or reported a protective effect (39). These inconsistencies may stem from differences in drug subtypes,

patient characteristics, and methodological design. Importantly, the

observational design of most included studies (33,36,37,39) limits causal inference and leaves room for residual confounding.

Some studies also examined the repurposing of non-conventional agents.

For instance, in vitro analyses of chlorpromazine and prazosin revealed

cytotoxic effects against liver cancer cells (38), though clinical application remains premature. Additionally, the

adjunctive use of ARBs with radiofrequency ablation was associated with better

outcomes in HCC patients (36), suggesting a potential role in combined treatment strategies.

In summary, while specific antihypertensive drugs—especially RAS

inhibitors and diuretics—may impact HCC risk or progression, findings are

heterogeneous across drug types and populations. These discrepancies likely

reflect variations in underlying liver conditions, genetic backgrounds, drug

mechanisms, and study quality (27,33,35,36,39,40). Carefully designed longitudinal studies are needed to clarify causality

and identify which patient populations may benefit—or be harmed—by specific

antihypertensive therapies in the context of liver cancer.

Recommendations of the Studies

To guide future research and clinical

decision-making, Table 6 summarizes the key recommendations and insights from

each included study, highlighting suggested directions for improving

antihypertensive use in the context of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

prevention and management.

The reviewed evidence collectively underscores the importance of cautious

interpretation regarding the association between antihypertensive medications

and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) risk. Several studies (27,35,36,38–40) suggest that specific drug classes—including thiazide diuretics,

Beta-blockers, ARBs, and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors—may

influence HCC risk, either positively or negatively. These preliminary

associations highlight the need for further exploration through rigorously

designed prospective studies and randomized controlled trials.

Concurrently, multiple authors (33,34,40) advocate against modifying existing clinical guidelines based solely on

these early findings. Instead, they emphasize maintaining standard cancer

prevention approaches while expanding future research to incorporate broader

risk factors such as genetic predispositions, lifestyle behaviors, and

socioeconomic determinants. Methodological refinements—including the use of

standardized data collection protocols, inclusion of diverse patient

populations, and multi-national study designs—are vital for improving the

reliability and generalizability of future evidence (34).

Table 6. Key recommendations of selected studies.

|

References

|

Recommendations

|

Key

Insights

|

|

(27)

|

Thiazide

diuretics may reduce HCC risk; Beta-blockers may increase it. Consider

individual risk factors and personalize treatment. Further studies are

needed.

|

Potential

drug-specific impact on HCC risk; need for personalized treatment and further

research.

|

|

(33)

|

No protective

effect of ACE inhibitors or Beta-blockers against liver cancer. Continue

using them for cardiovascular indications, not cancer prevention. Emphasize

established preventive strategies.

|

Antihypertensives

not indicated for cancer prevention; focus on established prevention (e.g.,

alcohol reduction, hepatitis management).

|

|

(34)

|

Recommendations

for future research: improve cohort diversity, ensure follow-up, analyze

broader risk factors, and conduct international, standardized studies.

|

Methodological

improvements to enhance validity and generalizability of findings.

|

|

(35)

|

Need for

prospective studies on renin-angiotensin system inhibitors for liver

protection. Encourage tailored approaches in high-risk patients.

|

Possible

protective role of RAS inhibitors; importance of personalized medicine and

longitudinal studies.

|

|

(36)

|

ARBs may be

beneficial in HCC patients undergoing RFA. Recommend further RCTs to confirm

efficacy and safety.

|

Potential

adjunct role for ARBs in HCC treatment; requires validation through RCTs.

|

|

(38)

|

Further studies

on chlorpromazine and prazosin for HCC treatment, including mechanism

exploration. Repurposing may expedite therapeutic development.

|

Drug

repurposing opportunity; need for mechanistic and clinical studies.

|

|

(39)

|

Recommend

further clinical trials on Beta-blockers' survival benefits and their

mechanisms in HCC. Investigate long-term use.

|

Investigate

Beta-blockers' therapeutic potential and long-term outcomes.

|

|

(40)

|

Recommend

future studies on long-term cancer risks of antihypertensives, especially

diuretics and ARBs. Consider lifestyle and genetics. Don’t change clinical

guidelines yet.

|

Cautious

interpretation of current findings; need for comprehensive risk assessment

and further validation.

|

Clinical Implications of the Study

This review underscores the importance of

considering both drug class and patient-specific factors when evaluating the

potential oncologic effects of antihypertensive medications. Among these,

agents targeting the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) may play a particularly

favorable role, especially in individuals with preexisting liver conditions.

Non-selective β-blockers also showed promise in reducing liver cancer

mortality in patients already diagnosed with HCC.

By contrast, diuretics demonstrated inconsistent effects, with some evidence

suggesting benefit while other studies reported increased cancer

risk—emphasizing the need for individualized therapeutic decisions based on

clinical context. Overall, these findings suggest the potential to expand the

therapeutic scope of certain antihypertensive drugs, though careful patient

selection and further validation are essential before clinical application.

Limitations

This review incorporates studies with considerable methodological and

clinical heterogeneity. Included studies range from randomized controlled

trials to observational cohort analyses and in vitro experimental research. A

notable limitation is the frequent reliance on prescription databases rather

than direct confirmation of medication adherence, which may lead to

misclassification of exposure. Additionally, several studies lacked detailed

clinical or lifestyle data, increasing the risk of residual confounding.

Confounding by indication—where the underlying reason for prescribing an

antihypertensive (e.g., cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis) may itself

influence liver cancer risk—was a common challenge in observational studies and

often not adequately controlled for. Selection bias was also a concern,

particularly in studies using region-specific or institution-based cohorts

(e.g., UK-only populations or U.S. veterans), which may not reflect broader

patient demographics. Furthermore, immortal time bias—where patients must

survive a certain period to receive treatment and thus appear to have better

outcomes—may have affected studies lacking clearly defined exposure windows and

time-to-treatment analyses.

Other issues included small sample sizes in certain studies, variations

in follow-up duration, differences in liver disease staging, and inconsistent

classification of antihypertensive drug categories. These limitations

complicate direct comparisons across studies and emphasize the need for

cautious interpretation. Future research should aim to address these biases

through more rigorous study designs, ideally using prospective, longitudinal

data with standardized outcome definitions.

Conclusion

This systematic review highlights the complex and nuanced

associations between antihypertensive drug use and hepatocellular carcinoma. Certain classes—most notably RAS inhibitors and

non-selective β-blockers—emerge as promising candidates for further

exploration in cancer prevention or adjunctive therapy, though definitive

conclusions remain premature. Mixed results for other drug types, such as

diuretics and selective β-blockers, reflect underlying heterogeneity

across study populations, designs, and outcome measures. The evidence,

though promising in parts, is tempered by significant methodological

limitations that prevent definitive conclusions.

Nevertheless, these findings offer a foundation for future research and suggest

a potential role for repurposing certain antihypertensive agents in liver

cancer prevention and treatment. To move the field forward, high-quality,

long-term clinical trials that incorporate diverse populations and standardized

methodologies are essential. These efforts will help determine whether specific

antihypertensive therapies can be safely and effectively integrated into

personalized strategies for patients at risk for or living with HCC.

Author contribution

SN developed the methodology and wrote the methodology

section. SN also conducted data extraction using a predesigned Excel

spreadsheet, capturing key study details, including study design, patient

population, type of antihypertensive medications used, liver cancer outcomes,

and major findings. Additionally, SN oversaw the entire review process

and coordinated the writing of the manuscript. FZ independently verified

50% of the extracted data to ensure accuracy and consistency. FZ also

wrote the results section, contributed to the final review of the manuscript,

played a role in developing the study design, and assisted in refining the

methodology section. AN contributed to refining the search strategy,

participated in the full-text review process, and assisted in synthesizing the

extracted data. AN also built the tables and diagrams for the manuscript

and helped review the methodology section. PD independently conducted

the title and abstract screening using Rayyan software, ensuring the initial

selection of studies. PD also conducted the full-text review for studies

meeting the inclusion criteria and wrote the discussion section. FT

independently verified 50% of the extracted data alongside MA to enhance

data accuracy. FT also contributed to refining the study methodology and

participated in manuscript revisions. MR wrote the introduction section

and assisted in optimizing the search strategy. MR also played a role in

screening full-text articles and contributed to drafting and reviewing the

discussion section. ML independently conducted the title and abstract

screening using Rayyan software, ensuring the initial selection of studies. ML

also wrote the conclusion section and participated in discussions regarding

study inclusion and exclusion criteria. JT contributed to writing the

discussion section and provided critical revisions to improve clarity and

coherence. JT also participated in reviewing the final manuscript to

ensure consistency and accuracy. SS played a role in the quality

assessment of the included studies and assisted in synthesizing the extracted

data. SS also contributed to reviewing the discussion and conclusion

sections to ensure alignment with the study objectives. All authors contributed

to the conception and design of the study, provided input on data

interpretation, and participated in manuscript revisions. All authors approved

the final version before submission.

Funding

There is no funding.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

Pranali M Wandile MC.

Hypertension and comorbidities: A silent threat to global health. Hypertension

and Comorbidities,;1(1):1-7. 2024 Feb 6;1(1):1–7.

2. Zhou B,

Perel P, Mensah GA, Ezzati M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective

interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol.

2021 Nov 1;18(11):785.

3. Kjeldsen

SE. Hypertension and cardiovascular risk: General aspects. Pharmacol Res. 2018

Mar 1;129:95–9.

4. Zhou B,

Bentham J, Di Cesare M, Bixby H, Danaei G, Cowan MJ, et al. Worldwide trends in

blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based

measurement studies with 19·1 million participants. The Lancet. 2017 Jan

7;389(10064):37–55.

5. Farhadi F,

Aliyari R, Ebrahimi H, Hashemi H, Emamian MH, Fotouhi A. Prevalence of

uncontrolled hypertension and its associated factors in 50–74 years old Iranian

adults: a population-based study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023 Dec 1;23(1):1–10.

6. Kibone W,

Bongomin F, Okot J, Nansubuga AL, Tentena LA, Nuwamanya EB, et al. High blood

pressure prevalence, awareness, treatment, and blood pressure control among

Ugandans with rheumatic and musculoskeletal disorders. PLoS One. 2023 Aug

1;18(8):e0289546.

7. Oh JH, Jun

DW. The latest global burden of liver cancer: A past and present threat. Clin

Mol Hepatol. 2023 Apr 1;29(2):355.

8. Yao Z, Dai C, Yang J, Xu M, Meng H, Hu X, Lin N. Time-trends in

liver cancer incidence and mortality rates in the U.S. from 1975 to 2017: a

study based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. J

Gastrointest Oncol. 2023 Feb 28;14(1):312-324.

9. Oster JR,

Materson BJ, Perez-Stable E. Antihypertensive Medications. South Med J. 2023

May 8; 77(5):621–30.

10. Smith SM,

Winterstein AG, Gurka MJ, Walsh MG, Keshwani S, Libby AM, et al. Initial

Antihypertensive Regimens in Newly Treated Patients: Real World Evidence From the OneFlorida+ Clinical Research Network. J Am Heart

Assoc. 2023 Jan 3;12(1):26652.

11. Oster JR,

Materson BJ, Perez-Stable E. Antihypertensive Medications. South Med J. 2023

May 8;77(5):621–30.

12. Chrysant SG, Frohlich ED. Side effects of antihypertensive drugs.

Am Fam Physician. 1974 Jan;9(1):94-101.

13. Smith DK, Lennon RP, Carlsgaard PB. Managing Hypertension Using

Combination Therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2020 Mar 15;101(6):341-349.

14. Shen D, Song S, Hu J, Cai X, Zhu Q, Zhang Y, Ma R, Zhou P, Zhang Z,

Hong J, Li N. The potential of spironolactone to mitigate the risk of

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in hypertensive populations: evidence from a

cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Sep 1;37(9):1010-1020.

15. Dang C,

Wang R, Shi Y, Liu P, Wang X, Liu J, et al. Genetically proxied therapeutic

effect of antihypertensive drug use, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer’s risk:

a drug-target Mendelian randomization study. BMC Cancer. 2025 Dec 1;25(1):1125.

16. Yang R,

Zhang Y, Liao X, Yao Y, Huang C, Liu L. The Relationship Between

Anti-Hypertensive Drugs and Cancer: Anxiety to be Resolved in Urgent. Front

Pharmacol. 2020 Dec 14;11:610157.

17. Franchi M,

Torrigiani G, Kjeldsen SE, Mancia G, Corrao G. Long-term exposure to

antihypertensive drugs and the risk of cancer occurrence: evidence from a large

population-based study. J Hypertens. 2024 Dec 1;42(12):2107–14.

18. Loosen SH,

Schöler D, Luedde M, Eschrich J, Luedde T, Gremke N, et al. Antihypertensive

Therapy and Incidence of Cancer. J Clin Med. 2022 Nov 1;11(22):6624.

19. Tadic M,

Cuspidi C, Belyavskiy E, Grassi G. Intriguing relationship between

antihypertensive therapy and cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2019 Mar 1; 141:501–11.

20. Wang S, Xie

L, Zhuang J, Qian Y, Zhang G, Quan X, et al. Association between use of

antihypertensive drugs and the risk of cancer: a population-based cohort study

in Shanghai. BMC Cancer. 2023 Dec 1;23(1):425.

21. Watanabe T,

Barker TA, Berk BC. Angiotensin II and the endothelium: Diverse signals and

effects. Hypertension. 2005 Feb 1;45(2):163–9.

22. Zhang S,

Cao M, Hou Z, Gu X, Chen Y, Chen L, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitors have adverse effects in anti-angiogenesis therapy for hepatocellular

carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2021 Mar 3;501:147–61.

23. Morris ZS,

Saha S, Magnuson WJ, Morris BA, Borkenhagen JF, Ching A, et al. Increased Tumor

Response to Neoadjuvant Therapy Among Rectal Cancer Patients Taking

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors or Angiotensin Receptor Blockers.

Cancer. 2016 Aug 15;122(16):2487.

24. Alcocer LA,

Bryce A, De Padua Brasil D, Lara J, Cortes JM, Quesada D, et al. The Pivotal

Role of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor

Blockers in Hypertension Management and Cardiovascular and Renal Protection: A

Critical Appraisal and Comparison of International Guidelines. American Journal

of Cardiovascular Drugs. 2023 Nov 1;23(6):663.

25. Ho CM, Lee

CH, Lee MC, Zhang JF, Wang JY, Hu RH, et al. Comparative effectiveness of

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers

in chemoprevention of hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide high-risk cohort

study. BMC Cancer. 2018 Dec 10;18(1):401.

26. Chen R,

Zhou S, Liu J, Li L, Su L, Li Y, et al. Renin–angiotensin system inhibitors and

risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with hepatitis B virus

infection. Can Med Assoc J. 2024 Aug 12; 196(27):E931–9.

27. Wang Z, Lu

J, Hu J. Association between antihypertensive drugs and hepatocellular

carcinoma: A trans-ancestry and drug-target Mendelian randomization study.

Liver International. 2023 Jun 1;43(6):1320–31.

28. Ma C, Wang

Q, Man Y, Kemmner W. Cardiovascular medications in angiogenesis--how to avoid

the sting in the tail. Int J Cancer. 2012 Sep 15;131(6):1249–59.

29. Qi J,

Bhatti P, Spinelli JJ, Murphy RA. Antihypertensive medications and risk of

colorectal cancer in British Columbia. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Nov 7;14:1301423.

30. Fadil KHA,

Mahmoud EM, El-Ahl SAHS, Abd-Elaal AA, El-Shafaey AAAM, Badr MSEDZ, et al.

Investigation of the effect of the calcium channel blocker, verapamil, on the

parasite burden, inflammatory response and angiogenesis in experimental

Trichinella spiralis infection in mice. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2022 Mar 1;26:e00144.

31. Cho IJ,

Shin JH, Jung MH, Kang CY, Hwang J, Kwon CH, et al. Antihypertensive Drugs and

the Risk of Cancer: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2021 Feb 2; 10(4):771.

32. Yu H, Liu

Z, Wu Y, Zheng L, Wang K, Wu J, et al. Antihypertensive medications and cancer

risk: Evidence from 0.27 million patients with newly diagnosed hypertension.

Front Pharmacol. 2025 Jul 1; 16:1559604.

33. Hagberg KW,

Sahasrabuddhe V V., McGlynn KA, Jick SS. Does Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme

Inhibitor and β-Blocker Use Reduce the Risk of Primary Liver Cancer? A

Case-Control Study Using the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink.

Pharmacotherapy. 2016 Feb 1;36(2):187–95.

34. Kanwal F,

Khaderi S, Singal AG, Marrero JA, Asrani SK, Amos CI, et al. Risk

Stratification Model for Hepatocellular Cancer in Patients With

Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Dec 1;21(13):3296-3304.e3.

35. Kim KM, Roh

JH, Lee S, Yoon JH. Do renin-angiotensin system inhibitors reduce risk for

hepatocellular carcinoma?: A nationwide nested

case-control study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021 Jul 1;45(4):101510.

36. Facciorusso

A, Abd El Aziz MA, Cincione I, Cea UV, Germini A, Granieri S, et al.

Angiotensin Receptor 1 Blockers Prolong Time to Recurrence after Radiofrequency

Ablation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma patients: A Retrospective Study.

Biomedicines. 2020 Oct 1;8(10):1–13.

37. Miyahara K,

Nouso K, Miyake Y, Nakamura S, Obi S, Amano M, et al. Serum glycan as a

prognostic marker in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated

with sorafenib. Hepatology. 2014 Jan 1;59(1):355–6.

38. Harris S,

Nagarajan P, Kim K. The cytotoxic effects of prazosin, chlorpromazine, and

haloperidol on hepatocellular carcinoma and immortalized non-tumor liver cells.

Med Oncol. 2024 Apr 1 ;41(4).

39. Udumyan R,

Montgomery S, Duberg AS, Fang F, Valdimarsdottir U, Ekbom A, et al.

Beta-adrenergic receptor blockers and liver cancer mortality in a national

cohort of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 2020 May 3

[cited 2025 Apr 5];55(5):597–605.

40. Loosen SH,

Schöler D, Luedde M, Eschrich J, Luedde T, Gremke N, et al. Antihypertensive

Therapy and Incidence of Cancer. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, Vol 11,

Page 6624. 2022 Nov 8 [cited 2025 Apr 5];11(22):6624.

41. Cho IJ, Shin JH, Jung MH, Kang CY, Hwang J, Kwon CH, Kim W, Kim DH,

Lee CJ, Kang SH, Lee JH, Kim HL, Kim HM, Cho I, Lee HY, Chung WJ, Ihm SH, Kim

KI, Cho EJ, Sohn IS, Park S, Shin J, Ryu SK, Kim JY, Kang SM, Cho MC, Pyun WB,

Sung KC. Antihypertensive Drugs and the Risk of Cancer: A Nationwide Cohort

Study. J Clin Med. 2021 Feb 15;10(4):771.

42. Feng LH,

Sun HC, Zhu XD, Zhang SZ, Li KS, Li XL, Li Y, Tang ZY. Renin-angiotensin

inhibitors were associated with improving outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma

with primary hypertension after hepatectomy. Ann Transl Med. 2019

Dec;7(23):739.

43. Singh B, Cusick AS, Goyal A, et al. ACE Inhibitors. [Updated 2025

May 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing;

2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430896/